The Finish Line You Cannot Yet See: It’s a Marathon, Not A Sprint

As we roll into September and many of us send our children back into the high pressure, high stakes game of school, it’s a good time to remind ourselves that education is a long haul endeavour, it’s a marathon not a sprint.

Success in education is about learning not achieving, and improvement doesn’t occur on a daily basis. In fact, it may not come within the confined trap of a single year grade; an organizational system in which we have arbitrarily fixed and set as the timeline for specific skill acquisition, knowledge retention, and personal improvement. The trap of school grades, ten months, September to June is that, by its very nature, it forces parents and students to live in ‘daily emergency’. The daily emergency of THIS homework, THIS test, THIS project, which inevitably becomes THIS report card.

When the 100m finish line can be seen (June 2023) every stride between it and the start line (September 2022) is immensely significant. However, when we cannot see the finish line, when it’s many kilometres away, we shift our thinking and we shift our focus. We no longer care about each individual stride, but instead we use a far more holistic approach; we develop a plan, and create a strategy that is process-oriented; one that will get us to the end. So instead of living this school year in the ‘daily emergency’, think about the long haul, the finish line that you cannot yet see. Think about where you’d like your child to be in five years. Ask yourself which is more important to you - that you scramble around and stay up late with your child to ensure that the project she “forgot about” is still perfectly completed, or that she is ill-prepared, experiences disappointment, but in turn develops better strategies for organization and time management? Is it more important that you do sight word cards and homework sound-skill sheets daily so that your son can decode words and is considered “a reader” at the end of kindergarten, or that through engaging books and connected time with older readers (parents, grandparents, family, reading buddies) the joy of reading is so carefully nurtured that it sticks with him well beyond high school?

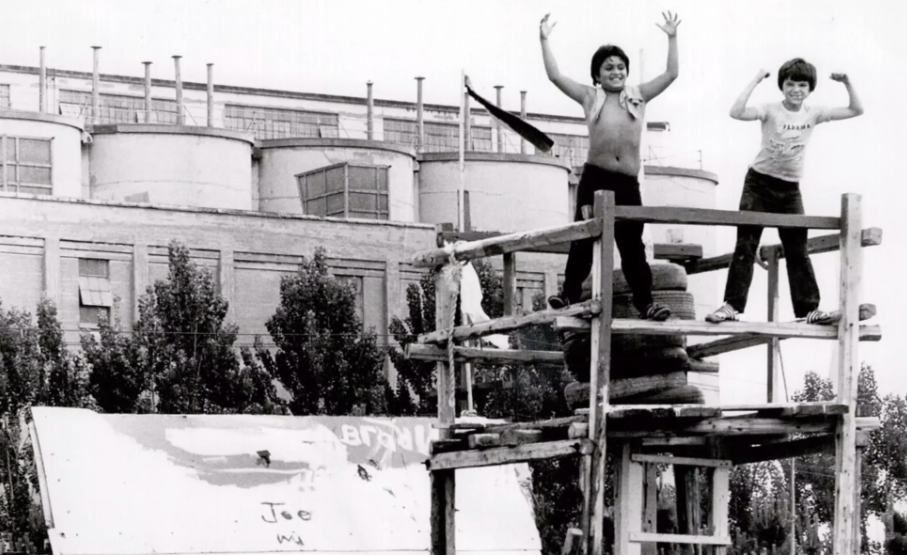

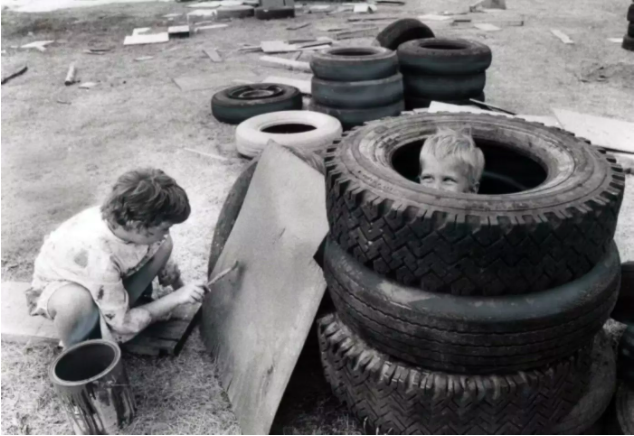

When we live in the ‘daily emergency’ and treat learning as a sprint, we also fail to teach our children that the road to excellence is in fact a long one. Unit tests, culminating assignments/projects, and even report cards continue to reflect our “fast-food”, instantaneous society. Text messaging, online shopping, Netflix. Everything comes to us quickly, and requires less and less effort. The expectation that students will have not only learned how to solve algebraic equations, but that they can also apply that skill to new and changing contexts all within the one-month unit timeline is really no different. We are creating and reinforcing a belief that there can be instant knowledge and immediate mastery of a subject or skill. But acquiring any new skill, whether it’s solving equations or learning to print your letters, isn’t easy, and you have to work at it. Really work at it. It takes dedicated and patient practice to become good at anything. It takes continual refinement and repetition. In kindergarten, our printed letters most often start as all capitals. Some are big, some are small, and some are every size in between. Our pencil lines are wiggly, and crooked, and letters are even backwards. It takes many years of elementary school (and we all know adults still working on their penmanship) to refine that skill; to print consistently on the line, with uniform sizing, and precise spacing. It’s a long-haul endeavour. It’s a marathon. It’s not a kindergarten sprint. As parents, and as educators we fall victim to focusing on, and valuing the all too quick assessment (the mark, the report card grade, the report card comments). Instead, we need to focus on teaching our children, and teaching ourselves to delay gratification. To celebrate the long, gradual process of learning. When we do so, our children will become better students, but more importantly, better people. And I believe that is ultimately the finish line that we all hope to see.

It is time to go back to school.

But the finish line isn’t June.